A week ago, I wrote a post about the potential of crowdsourcing and the use of hashtags for gathering enhanced data on infection rates for Covid-19. Things have moved rapidly since then as companies, civil society organisations, international organisations, academics and donors have all developed countless initiatives to try to respond. Many of these initiatives seem to be more about the profile and profits of the organisations/entities involved than they do about making a real impact on the lives of those who will suffer most from Covid-19. Yesterday, I wrote another post on my fears that donors and governments will waste huge amounts of money, time and effort on Covid-19 to little avail, since they have not yet learnt the lessons of past failures.

I still believe that crowdsourcing could have the potential, along with many other ways of gathering data, to enhance decision making at this critical time. However the dramatic increase in the number of such initiatives gives rise to huge concern. Let us learn from past experience in the use of digital technologies in development, and work together in the interests of those who are likely to suffer the most. Eight issues are paramount when designing a digital tech intervention to help reduce the impact of Covid-19, especially through crowdsourcing type initiatives:

- Don’t duplicate what others are already doing

- Treat privacy and security very carefully

- Don’t detract from official and (hopefully) accurate information

- Keep it simple

- Ask questions that will be helpful to those trying to respond to the pandemic

- Ensure that there are at least some questions that are the same in all surveys if there are multiple initiatives being done by different organisations

- Work with a globally agreed set of terminology and hashtags (#)

- Collaborate and share

Don’t duplicate what others are already doing

As the very partial list of recent initiatives at the end of this post indicates, many crowdsourcing projects have been created across the world to gather data from people about infections and behaviours relating to Covid-19. Most of these are well-intentioned, although there will also be those that are using such means unscrupulously also to gather data for other purposes. Many of these initiatives ask very similar questions. Not only is it a waste of resources to design and build several competing platforms in a country (or globally), but individual citizens will also soon get bored of responding to multiple different platforms and surveys. The value of each initiative will therefore go down, especially if there is no means of aggregating the data. Competition between companies may well be an essential element of the global capitalist system enabling the fittest to accrue huge profits, but it is inappropriate in the present circumstances where there are insufficient resources available to tackle the very immediate responses needed across the world.

Treat privacy and security very carefully

Most digital platforms claim to treat the security of their users very seriously. Yet the reality is that many fail to protect the privacy of much personal information sufficiently, especially when software is developed rapidly by people who may not prioritise this issue and cut corners in their desire to get to market as quickly as possible. Personal information about health status and location is especially sensitive. It can therefore be hugely risky for people to provide information about whether they are infected with a virus that is as easily transmitted as Covid-19, while also providing their location so that this can then be mapped and others can see it. Great care should be taken over the sort of information that is asked and the scale at which responses are expected. It is not really necessary to know the postcode/zipcode of someone, if just the county or province will do.

Don’t detract from official and (hopefully) accurate information

Use of the Internet and digital technologies have led to a plethora of false information being propagated about Covid-19. Not only is this confusing, but it can also be extremely dangerous. Please don’t – even by accident – distract people from gaining the most important and reliable information that could help save their lives. In some countries most people do not trust their governments; in others, governments may not have sufficient resources to provide the best information. In these instances, it might be possible to work with the governments to ehance their capacity to deliver wise advice. Whatever you do, try to point to the most reliable globally accepted infomation in the most appropriate languages (see below for some suggestions).

Keep it simple

Many of the crowdsourcing initiatives currently available or being planned seem to invite respondents to complete a fairly complex and detailed list of questions. Even when people are healthy it could be tough for them to do so, and this could especially be the case for the elderly or digitally inexperienced who are often the most vulnerable. Imagine what it would be like for someone who has a high fever or difficulty in breathing trying to fill it in.

Ask questions that will be helpful to those trying to respond to the pandemic

It is very difficult to ask clear and unambiguous questions. It is even more difficult to ask questions about a field that you may not know much about. Always work with people who might want to use the data that your initiative aims to generate. If you are hoping, for example, to produce data that could be helpful in modelling the pandemic, then it is essential to learn from epidemiologists and those who have much experience in modelling infectious diseases. It is also essential to ensure that the data are in a format that they can actually use. It’s all very well producing beautful maps, but if they use different co-ordinate systems or boundaries from those used by government planners they won’t be much use to policy makers.

Ensure that there are at least some questions that are the same in all surveys if there are multiple initiatives being done by different organisations

When there are many competing surveys being undertaken by different organisations about Covid-19, it is important that they have some identical questions so that these can then be aggregated or compared with the results of other initiatives. It is pointless having multiple initiatives the results of which cannot be combined or compared.

Work with a globally agreed set of terminology and hashtags (#)

The field of data analytics is becoming ever more sophisticated, but if those tackling Covid-19 are to be able readily to use social media data, it would be very helpful if there was some consistency in the use of terminology and hashtags. There remains an important user-generated element to the creation of hashtags (despite the control imposed by those who create and own social media platforms), but it would be very helpful to those working in the field if some consistency could be encouraged or even recommended by global bodies and UN agencies such as the WHO and the ITU.

Collaborate and share

Above all, in these unprecendented times, it is essential for those wishing to make a difference to do so collaboratively rather than competitively. Good practices should be shared rather than used to generate individual profit. The scale of the potential impact, especially in the weakest contexts is immense. As a recent report from the Imperial College MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis notes, without interventions Covid-19 “would have resulted in 7.0 billion infections and 40 million deaths globally this year. Mitigation strategies focussing on shielding the elderly (60% reduction in social contacts) and slowing but not interrupting transmission (40% reduction in social contacts for wider population) could reduce this burden by half, saving 20 million lives, but we predict that even in this scenario, health systems in all countries will be quickly overwhelmed. This effect is likely to be most severe in lower income settings where capacity is lowest: our mitigated scenarios lead to peak demand for critical care beds in a typical low-income setting outstripping supply by a factor of 25, in contrast to a typical high-income setting where this factor is 7. As a result, we anticipate that the true burden in low income settings pursuing mitigation strategies could be substantially higher than reflected in these estimates”.

Resources

This concluding section provides quick links to generally agreed reliable and simple recommendations relating to Covid-19 that could be included in any crowdsourcing platform (in the appropriate language), and a listing of just a few of the crowdsourcing initiatives that have recently been developed.

Recommended reliable information on Covid-19

- WHO resources

- Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

- Africa Centres for Disease Control (very slow to download – can someone urgently please help them get better connectivity)

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- UK National Health Service Advice for Everyone – and good graphics from the BBC

- Survey instrument questions developed and shared by Imperial College MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis (UK)

Remember the key WHO advice adopted in various forms by different governments:

- Wash your hands frequently

- Maintain social distancing

- Avoid touching eyes, nose and mouth

- If you have fever, cough and difficulty breathing, seek medical care early

A sample of crowdsourcing initiatives

Some of the many initiatives using crowdsourcing and similar methods to generate data relating to Covid-19 (many of which have very little usage):

- Global/Generic

- Redaktor (mainly European)

- Folding@Home

- Safecast – an international volunteer driven non-profit organization whose goal is to create useful, accessible, and granular environmental data

- WhatsApp Coronoavirus Information Hub

- Good Judgement Open Platform

- Metaculus

- Argentina

- Coronavirus Argentina (very little usage)

- France

- Coronavirus in Toulouse (very little usage)

- Italy

- India

- Covid-19 in India (press report)

- Kenya

- Madagascar

- MDG – Covid 19 (very little usage)

- Nigeria

- Singapore

- South Africa

- Chatsworth (very litte usage)

- Spain

- Frena La Curva

- coronavirusmakers (very little usage)

- Sweden

- Corona Help (very little usage)

- Switzerland

- UK

- Let’s Beat Covid-19 – a million doctors need your help (anonymous survey)

- Covid Symptom Tracker – Guy’s and St Thomas’ Biomedical Research Centre

- Public Health England – UK Covid-19 update maps

- USA

- Covid 19 Connectus (very little usage)

- Covid Near You

- Opendemic (by students at Harvard and MIT)

Lists by others of relevant initiatives:

- Open Gov Partnership: Collecting open governments approaches to COVID-19

- NESTA: Mobilising collective inetlligence to tackle the COVID-19 threat

- Noel Patel’s (MIT) listing of 10 coronavirus dashboards

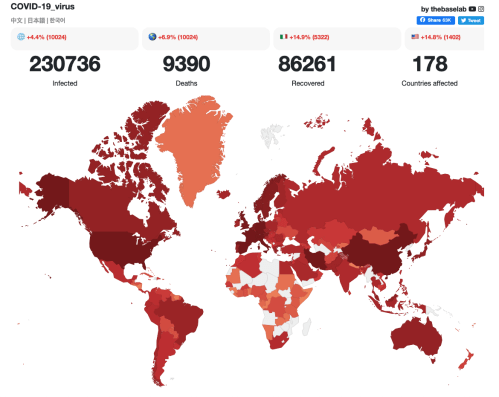

Global Covid-19 mapping and recording initiatives

The following are currently three of the best sourcs for global information about Covid-19 – although I do wish that they clarified that “infections” are only “recorded infections”, and that data around deaths should be shown as “deaths per 1000 people” (or similar density measures) and depicted on choropleth maps.

We are all going to be affected by Covid-19, and we must work together across the world if we are going to come out of the next year peacefully and coherently. The world in a year’s time will be fundamentally different from how it is now; now is the time to start planning for that future. The countries that will be most adversely affected by Covid-19 are not the rich and powerful, but those that are the weakest and that have the least developed healthcare systems. Across the world, many well-intentioned people are struggling to do what they can to make a difference in the short-term, but many of these initiatives will fail; most of them are duplicating ongoing activity elsewhere; many of them will do more harm than good.

We are all going to be affected by Covid-19, and we must work together across the world if we are going to come out of the next year peacefully and coherently. The world in a year’s time will be fundamentally different from how it is now; now is the time to start planning for that future. The countries that will be most adversely affected by Covid-19 are not the rich and powerful, but those that are the weakest and that have the least developed healthcare systems. Across the world, many well-intentioned people are struggling to do what they can to make a difference in the short-term, but many of these initiatives will fail; most of them are duplicating ongoing activity elsewhere; many of them will do more harm than good. “A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and

“A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and

istors should, though, be warned that passports/identity cards are needed to enter, and that payment (currently US$43 per foreign visitor) is required by card rather than cash. It was amusing to reflect that the introduction of digital payment means has led to lengthy queues; although it may have reduced fraud, it has certainly lengthened the time it takes visitors to enter the park!

istors should, though, be warned that passports/identity cards are needed to enter, and that payment (currently US$43 per foreign visitor) is required by card rather than cash. It was amusing to reflect that the introduction of digital payment means has led to lengthy queues; although it may have reduced fraud, it has certainly lengthened the time it takes visitors to enter the park! It was great to be part of the DFID-funded technology for education

It was great to be part of the DFID-funded technology for education

It was a great honour to have been invited – a few hours beforehand – to give one of the inaugural WSIS TalkX presentations last Thursday evening as

It was a great honour to have been invited – a few hours beforehand – to give one of the inaugural WSIS TalkX presentations last Thursday evening as