It is always exciting submitting a book manuscript to a publisher, and today is no exception! I have at last finished with my editing and revisions, and sent the manuscript of Reclaiming ICT4D off to Oxford University Press. I just hope that they like it as much as I do! It is by no means perfect, but it is what I have been wanting to write for almost a decade now.

This is how it begins – I hope you like it:

“Chapter 1

A critical reflection on ICTs and ‘Development’

This book is about the ways through which Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have become entwined with both the theory and the practice of ‘development’. Its central argument is that although the design and introduction of such technologies has immense potential to do good, all too often this potential has had negative outcomes for poor and marginalized people, sometime intended but more often than not unintended. Over the last twenty years, rather than reducing poverty, ICTs have actually increased inequality, and if ‘development’ is seen as being about the relative differences between people and between communities, then it has had an overwhelming negative impact on development. Despite the evidence to the contrary, I nevertheless retain a deep belief in the potential for ICTs to be used to transform the lives of the world’s poorest and most marginalized for the better. The challenge is that this requires a fundamental change in the ways that all stakeholders think about and implement ICT policies and practices. This book is intended to convince these stakeholders of the need to change their approaches.

It has its origins in the mid-1970s, when I learnt to program in Fortran, and also had the privilege of undertaking field research in rural India. The conjuncture of these two experiences laid the foundations for my later career, which over the last twenty years has become increasingly focused on the interface between Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) on the one hand, and the idea of ‘development’ on the other. The book tells personal stories and anecdotes (shown in a separate font). It draws on large empirical data sets, but also on the personal qualitative accounts of others. It tries to make the complex theoretical arguments upon which it is based easy to understand. Above all, it has a practical intent in reversing the inequalities that the transformative impacts of ICTs have led to across the world.

I still remember the enjoyment, but also the frustrations, of using punch cards, with 80 columns, each of which had 12 punch locations, to write my simple programs in Fortran. The frustration was obvious. If you made just one tiny mistake in punching a card, the program would not run, and you would have to take your deck of cards away, make the changes, and then submit the revised deck for processing the next day. However, there was also something exciting about doing this. We were using machines to generate new knowledge. They were modern. They were the future, and we dreamt that they might be able to change the world, to make it a better place. Furthermore, there was something very pleasing in the purity and accuracy that they required. It was my fault if I made a mistake; the machine would always be precise and correct. These self-same comments also apply to the use of ICTs today. Yes, they can be frustrating, as when one’s immensely powerful laptop or mobile ‘phone crashes, or the tedium of receiving unwanted e-mails extends the working day far into time better spent doing other things, but at the same time the interface between machines and modernity conjures up a belief that we can use them to do great things – such as reducing poverty.

Figure 1.1 Modernity and the machine: Cambridge University Computer Laboratory in the early 1970s.

Source: University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory (1999)

In 1976 and 1977 I had the immense privilege of undertaking field research in the Singbhum District of what was then South Bihar, now Jharkhand, with an amazing Indian scholar, Sudhir Wanmali, who was undertaking his PhD about the ‘hats’, or periodic markets, where rural trade and exchange occurred in different places on each day of the week (Figure 1.2). Being ‘in the field’ with him taught me so much: the haze and smell of the woodsmoke in the evenings; the intense colours of rural India; the rice beer served in leaf cups at the edges of the markets towards the end of the day; the palpable tensions caused by the ongoing Naxalite rising (Singh, 1995); the profits made by mainly Muslim traders from the labour of Adivasi, tribal villagers, in the beautiful forests and fields of Singbhum; the creaking oxcarts; and the wonderful names of the towns and villages such as Hat Gamharia, Chakradharpur, Jagannathpur, and Sonua. Most of all, though, it taught me that ‘development’ had something powerful to do with inequality. I still vividly recall seeing rich people picnicking in the lush green gardens of the steel town of Jamshedpur nearby, coming in their smart cars from their plush houses, and then a short distance away watching and smelling blind beggars shuffling along the streets in the hope of receiving some pittance to appease their hunger. The ever so smart, neatly pressed, clothes of the urban elite at the weekends contrasted markedly with the mainly white saris, trimmed with bright colours, that scarcely covered the frail bodies of the old rural women in the villages where we worked during the week. Any development that would take place here had to be about reducing the inequalities that existed between these two different worlds within the world of South Bihar. This made me look at my own country, at the rich countries of Europe, and it made me all the more aware of two things: not only that inequality and poverty were also in the midst of our rich societies; but also that the connections between different countries in the world had something to do with the depth of poverty, however defined, in places such as the village of Sonua, or the town of Ranchi in South Bihar.

Figure 1.2: hat, or rural periodic market at Hat Gamharia, in what was then South Bihar, 1977  Source: Author

Source: Author

Between the mid-1970s and the mid-2010s my interests in ICTs, on the one hand, and ‘development’ on the other, have increasingly fascinated and preoccupied me. This book is about that fascination. It shares stories about how they are connected, how they impinge on and shape each other. I have been fortunate to have been involved in many initiatives that have sought to involve ICTs in various aspects of ‘development’. In the first instance, my love of computing and engineering, even though I am a geographer, has always led me to explore the latest technological developments, from electronic typewriters that could store a limited number of words, through the first Apple computers, to the Acorn BBC micro school and home computer launched in 1981, using its Basic BASIC programming language, and now more recently to the use of mobile ‘phones for development. I was fascinated by the potential for computers to be used in schools and universities, and I learnt much from being involved with the innovative Computers in Teaching initiative Centre for Geography in the 1990s (see Unwin and Maguire, 1990). During the 2000s, I then had the privilege of leading two challenging international initiatives that built on these experiences. First, between 2001 and 2004 I led the UK Prime Minister’s Imfundo: Partnership for IT in Education initiative, based within the Department for International Development (UK Government Web Archive 2007), which created a partnership of some 40 governments, private sector and civil society organisations committed to using ICTs to enhance the quality and quantity of education in Africa, particularly in Kenya, South Africa and Ghana. Then in the latter 2000s, I led the World Economic Forum’s Partnerships for Education initiative with UNESCO, which sought to draw out and extend the experiences gained through the Forum’s Global Education Initiative’s work on creating ICT-based educational partnerships in Jordan, Egypt, Rajasthan and Palestine (Unwin and Wong, 2012). Meanwhile, between these I created the ICT4D (ICT for Development) Collective, based primarily at Royal Holloway, University of London, which was specifically designed to encourage the highest possible quality of research in support of the poorest and most marginalized. Typical of the work we encouraged was another partnership-based initiative, this time to develop collaborative research and teaching in European and African universities both on and through the use of ICTs. More recently, between 2011 and 2015 I had the privilege of being Secretary General of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation, which is the membership organisation of governments and people in the 53 countries of the Commonwealth, enhancing the use of ICTs for development.

Two things have been central to all of these initiatives: first a passionate belief in the practical role of academics and universities in the societies of which they are a part, at all scales from the local to the international; and second, recognition of the need for governments, the private sector and civil society to work collaboratively together in partnerships to help deliver effective development impacts. The first of these builds fundamentally on the notion of Critical Theory developed by the Frankfurt School (Held, 1980), and particularly the work of Jürgen Habermas (1974, 1978) concerning the notion of knowledge constitutive interests and the complex inter-relationships between theory and practice. The next section therefore explores why this book explicitly draws on Critical Theory in seeking to understand the complex role and potential of ICTs in and for development. Section 1.2 thereafter then draws on the account above about rural life in India in the 1970s to explore in further detail some of the many ways in which the term ‘development’ has been, and indeed still is, used in association with technology.”

This was an opportunity for me to explore the relevance to the European context of some of my ideas about ICTs and inequality gleaned from research and practice in Africa and Asia. In essence, my argument was that we need to balance the economic growth agenda with much greater focus on using ICTs to reduce inequalities if we are truly to use ICTs to support greater European integration. To do this, I concluded by suggesting that we need to concentrate on seven key actions:

This was an opportunity for me to explore the relevance to the European context of some of my ideas about ICTs and inequality gleaned from research and practice in Africa and Asia. In essence, my argument was that we need to balance the economic growth agenda with much greater focus on using ICTs to reduce inequalities if we are truly to use ICTs to support greater European integration. To do this, I concluded by suggesting that we need to concentrate on seven key actions:

The ITU is preparing a new book, provisionally to be entitled “ICT4SDGs: Economic Growth, Innovation and

The ITU is preparing a new book, provisionally to be entitled “ICT4SDGs: Economic Growth, Innovation and I have been invited to lead on a 6,000 word chapter, provisionally entitled “Sustainability in Development: Critical Elements” that has an initial summary as follows: “the chapter identifies how ICTs engage with the sustainability agenda and the various elements of the ecosystem (such as: education, finance/capital, infrastructure, policy, market, culture/environment, opportunities) and the stakeholders that are indispensable for ensuring resilient and sustainable development activities in developing countries in spite of some chronic shortages coupled with fast changing and fluid situations that can negatively hamper the efforts”.

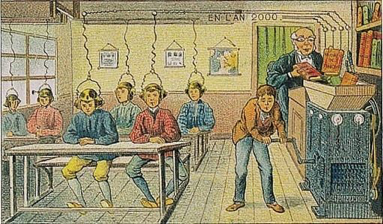

I have been invited to lead on a 6,000 word chapter, provisionally entitled “Sustainability in Development: Critical Elements” that has an initial summary as follows: “the chapter identifies how ICTs engage with the sustainability agenda and the various elements of the ecosystem (such as: education, finance/capital, infrastructure, policy, market, culture/environment, opportunities) and the stakeholders that are indispensable for ensuring resilient and sustainable development activities in developing countries in spite of some chronic shortages coupled with fast changing and fluid situations that can negatively hamper the efforts”. First, the term EdTech places the emphasis on the technology rather than the educational and learning outcomes. Far too many initiatives that have sought to introduce technology systematically into education have failed because they have focused on the technology rather than on the the education. The use of the term EdTech therefore places emphasis on a failed way of thinking. Technology will only be of benefit for poor and marginalized people if it is used to deliver real learning outcomes, and this is the core intended outcome of any initiative. It is the learning that matters, rather than the technology.

First, the term EdTech places the emphasis on the technology rather than the educational and learning outcomes. Far too many initiatives that have sought to introduce technology systematically into education have failed because they have focused on the technology rather than on the the education. The use of the term EdTech therefore places emphasis on a failed way of thinking. Technology will only be of benefit for poor and marginalized people if it is used to deliver real learning outcomes, and this is the core intended outcome of any initiative. It is the learning that matters, rather than the technology. Second, it implies that there is such a thing as Educational Technology. The reality is that most technology that is used in schools or for education more widely has very little to do specifically with education or learning. Word processing and presentational software, spreadsheets, and networking software are nothing specifically to do with education, although they are usually what is taught to teachers in terms of IT skills! Such software is, after all, usually called Office software, as in Microsoft Office, or Open Office. Likewise, on the hardware side, computers, mobile phones and electronic whiteboards are not specifically educational but are rather more general pieces of technology that companies produce to generate a profit. Learning content, be it open or proprietary, is perhaps the nearest specifically educational technology that there is, but people rarely even think of this when they use the term EdTech!

Second, it implies that there is such a thing as Educational Technology. The reality is that most technology that is used in schools or for education more widely has very little to do specifically with education or learning. Word processing and presentational software, spreadsheets, and networking software are nothing specifically to do with education, although they are usually what is taught to teachers in terms of IT skills! Such software is, after all, usually called Office software, as in Microsoft Office, or Open Office. Likewise, on the hardware side, computers, mobile phones and electronic whiteboards are not specifically educational but are rather more general pieces of technology that companies produce to generate a profit. Learning content, be it open or proprietary, is perhaps the nearest specifically educational technology that there is, but people rarely even think of this when they use the term EdTech! Third, it is fascinating to consider why the term EdTech has been introduced to replace others such as e-learning or ICT for education (ICT4E) which clearly place the emphasis on the learning and the education. The main reason for this is that the terminology largely reflects the interests of private sector technology companies, and especially those from the US. The interests underlying the terminology are a fundamental part of the problem. EdTech is being used and sold as a concept primarily so that companies can sell technology that has little specifically to do with education, and indeed so that researchers can be funded to study its impact!

Third, it is fascinating to consider why the term EdTech has been introduced to replace others such as e-learning or ICT for education (ICT4E) which clearly place the emphasis on the learning and the education. The main reason for this is that the terminology largely reflects the interests of private sector technology companies, and especially those from the US. The interests underlying the terminology are a fundamental part of the problem. EdTech is being used and sold as a concept primarily so that companies can sell technology that has little specifically to do with education, and indeed so that researchers can be funded to study its impact!

Source: Author

Source: Author For those who would like a little more detail, this is the provisional Table of Contents – subject of course to revision:

For those who would like a little more detail, this is the provisional Table of Contents – subject of course to revision:

One of the most interesting aspects of my visit to Pakistan in January this year was the informal, anecdotal information that I gathered about educational change in the Punjab, and in particular DFID’s flagship

One of the most interesting aspects of my visit to Pakistan in January this year was the informal, anecdotal information that I gathered about educational change in the Punjab, and in particular DFID’s flagship  The reality, as it was relayed to me, is very different. Clearly, these are anecdotes, but the following were the main points that my colleagues mentioned:

The reality, as it was relayed to me, is very different. Clearly, these are anecdotes, but the following were the main points that my colleagues mentioned: For me, though, the most important thing was what people said about the actual delivery of school building on the ground, and how it did little to counter the power of landlords. I was, for example, told on several occasions that some landowners used the newly built school buildings as cattle byres, and that the first thing that teachers had to do in the morning was to clean out all of the manure that had accumulated overnight before they could start teaching. More worryingly, I was given one account whereby my interlocutor assured me that on more than one occasion a landlord’s thugs had beaten teachers and threatened to kill them if they ever returned to their new school buildings. The reality and threat of rape for women teachers was a common complaint. Again, I never witnessed this, but the assuredness of those who told me these stories, many of whom I deeply trust, makes me inclined to believe them. This is the perceived reality of education reform on the ground in Punjab.

For me, though, the most important thing was what people said about the actual delivery of school building on the ground, and how it did little to counter the power of landlords. I was, for example, told on several occasions that some landowners used the newly built school buildings as cattle byres, and that the first thing that teachers had to do in the morning was to clean out all of the manure that had accumulated overnight before they could start teaching. More worryingly, I was given one account whereby my interlocutor assured me that on more than one occasion a landlord’s thugs had beaten teachers and threatened to kill them if they ever returned to their new school buildings. The reality and threat of rape for women teachers was a common complaint. Again, I never witnessed this, but the assuredness of those who told me these stories, many of whom I deeply trust, makes me inclined to believe them. This is the perceived reality of education reform on the ground in Punjab. The ICT industry has for far too long been dominated by men, much to its disadvantage, and it is good that an increasing amount of publicity is being shed on the sexism that has come to dominate the sector more widely. In 2014, the Guardian newspaper ran an interesting series of reports on the subject, one of which was entitled “

The ICT industry has for far too long been dominated by men, much to its disadvantage, and it is good that an increasing amount of publicity is being shed on the sexism that has come to dominate the sector more widely. In 2014, the Guardian newspaper ran an interesting series of reports on the subject, one of which was entitled “ As a first step, I am issuing this call for all international organisations in the field of ICTs to issues guidelines on expected behaviour at their events. I prefer guidelines to codes, because codes generally require policing, and the imposition of penalties or sanctions should anyone be found guilty. In practice, this is extremely difficult to implement and enforce. Guidelines, instead, reflect expected norms, and should be acted upon by everyone participating in an event. If someone witnesses inappropriate behaviour, it should be their responsibility to take action to ensure that the perpetrator stops. In far too many cases, though, people at present do not take enough action, especially when the harassment is by someone senior in the sector. This has to change. We must all take collective responsibility for bringing an end to such behaviour, so that everyone can participate equally at international ICT events without fear of being harassed because of their gender or sexuality.

As a first step, I am issuing this call for all international organisations in the field of ICTs to issues guidelines on expected behaviour at their events. I prefer guidelines to codes, because codes generally require policing, and the imposition of penalties or sanctions should anyone be found guilty. In practice, this is extremely difficult to implement and enforce. Guidelines, instead, reflect expected norms, and should be acted upon by everyone participating in an event. If someone witnesses inappropriate behaviour, it should be their responsibility to take action to ensure that the perpetrator stops. In far too many cases, though, people at present do not take enough action, especially when the harassment is by someone senior in the sector. This has to change. We must all take collective responsibility for bringing an end to such behaviour, so that everyone can participate equally at international ICT events without fear of being harassed because of their gender or sexuality. To be sure, there are very complex cultural issues to be considered in any such discussion, but the fundamental aspect of harassment is that it is any behaviour that someone else considers to be unacceptable. Hence, we must all consider the other person’s cultural context in our actions and behaviours, rather than our own cultural norms. Just because something might be acceptable in our own culture, does not mean that it is acceptable in another person’s culture. Despite such complexities, some international organisations have indeed produced documents that can provide the basis for good practices in this area. Some of the most useful are:

To be sure, there are very complex cultural issues to be considered in any such discussion, but the fundamental aspect of harassment is that it is any behaviour that someone else considers to be unacceptable. Hence, we must all consider the other person’s cultural context in our actions and behaviours, rather than our own cultural norms. Just because something might be acceptable in our own culture, does not mean that it is acceptable in another person’s culture. Despite such complexities, some international organisations have indeed produced documents that can provide the basis for good practices in this area. Some of the most useful are: