Watching a video last Wednesday at UNESCO’s Mobile Learning Week produced by Huawei on the Fourth Industrial Revolution reminded me of everything that is problematic and wrong with the notion: it was heroic, it was glitzy, women were almost invisible, and above all it implied that technology was, and still is, fundamentally changing the world. It annoyed and frustrated me because it was so flawed, and it made me think back to when Klaus Schwab first gave me a copy of his book The Fourth Industrial Revolution in 2016. I read it, appreciated its superficially beguiling style, found much of it interesting, but realised that the argument was fundamentally flawed (for an excellent review, see Steven Poole’s 2017 review in The Guardian). Naïvely, I thought it was just another World Economic Forum publication that would fade away into insignificance on my bookshelves. How wrong I was! Together with the equally problematic notion of Frontier Technologies (see my short critique), it has become a twin-edged sword held high by global corporations and the UN alike to describe and justify the contemporary world, and their attempts to change it for the better. Whilst I have frequently challenged the notion and construction of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, I have never yet put togther my thoughts about it in a brief, easy to read format. Huawei’s video has provoked this response built around five fundamental problems.

Problem 1: a belief that technology has changed, and is changing the world

All so-called industrial revolutions are based on the fundamentally incorrect assumption that technology is changing the world. With respect to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Schwab thus claims that “The premise of this book is that technology and digitization will revolutionalize everything, making the overused and often ill-used adage “this time is different” apt. Simply put, major technological innovations are on the brink of fueling momentous change throughout the world – inevitably so” (Schwab, 2016, section 1.2; see also Schwab, 2015). The entire edifice of the Fourth Industriual Revolution is built on this myth. However, technology itself does not change anything. Technology is designed by people for particular purposes that serve very specific interests. It is these that change the world, and not the technology. The reductionist, instrumental and deterministic views inherent within most notions of a Fourth Industrial Revolution are thus highly problematic.

In the popular mind, each so-called industrial revolution is named after a particular technology: the first associated with mechanisation, water, steam power and railways in the late-18th and early-19th centuries; the second, mass production and assembly lines enabled by electricity in the late-19th and early-20th centuries; the third, computers and automation from the 1960s; and the fourth, often termed cyber-physical systems, based on the interconnectivity between physical, biological and digital spheres, from the beginning of the 21st century. However, all of these technologies were created by people to achieve certain objectives, usually to make money, become famous, or simply to overcome challenges. It is the same today. It is not the technologies that are changing the world, but rather the vision, ingenuity and rapaciousness of those who design, build and sell them. Humans still have choices. They can design technologies in the interests of the rich and powerful to make them yet richer and more powerful, or they can seek to craft technologies that empower and serve the interests of the poor and marginalised. Those developing technologies associated with so-called “smart cities” can thus be seen as marginalising those living in rural areas and in what might disparagingly be called “stupid villages”.

Problem 2: a revolutionary view of history

Academics (especially historians and geographers) have long argued as to whether human society changes in an evolutionary or a revolutionary way. There have thus been numerous debates as to how many agricultural revolutions there were that preceded or were associated with the so-called (first) industrial revolution (Overton, 1996). Much of this evidence suggests that whilst “revolutions” are nice, simple ideas to capture the essence of change, in reality they build on developments that have evolved over many years, and it is only when these come together and are reconfigured in new ways, to serve specific interests, that fundamental changes really occur.

For example, the Internet was initially used almost exclusively by academics, with the first e-mail systems being developed in the 1970s, and the World Wide Web in the 1980s, largely in an academic context. It was only when the commercial potential of these technologies was fully realised in the latter half of the 1990s that use of the Web really began to expand rapidly. In this context, most things associated with the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution actually seem to be extensions of ideas that existed very much earlier. The notion of integrated physical-biological systems is, for example, not something dramatically new in the 21st century, but rather has its genesis in the notion of cybernetic organisms, or cyborgs, at least as early as the 1960s.

More importantly, the main drivers of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution go back many centuries, and each previous “revolution” was merely an evolving process to find new ways of configuring them. If there was any fundamental “revolutionary” change, it occurred in the rise of individualism and the Enlightenment during the 17th century in Europe. Even this had many precursors. Fully to understand the digital economies of the 21st century, we need to appreciate the shift in balance from communal to individual interests some four centuries previously. Once it was appreciated that individual investment in the means of production could generate greater productivity and profit, and institutions were set in place to enable this (such as land enclosure, patent law and copyright), then the scene was set for “money bent upon accretion of money”, or capital (Marx, 1867), to become the overaching driver of an increasingly global economic system in the centuries that followed. The interests underlying the so called Fourth Industrial Revolution are largely the same as those driving the economic, social and political systems of the previous 400 years: market expansion and a reduction of labour costs through the use of technology. It is these interests, rather than the technologies themeselves that are of most importance.

Problem 3: an élite view of history

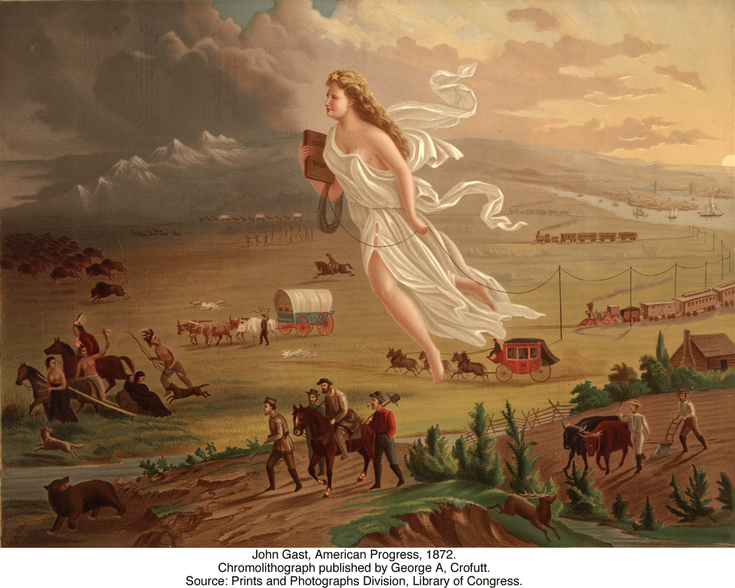

The notion of industrial revolutions is also largely an expression of an élite view of history. It is about, and written by, the élites who shape them and enable them. It is about the owners of the factories rather than the labourers, it is about innovative geniuses rather than the peasants labouring to produce food for them, and it is about the wise politicians who see the potential of these technologies to transform the world in their own image. Certainly, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is premised on an assumption that global corporations and brilliant innovative minds are driving the technological revolution that will change the world for what they see as being the better. It is also no coincidence that the World Economic Forum’s Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution was established in the USA, and that most of its proponents seem to be drawn from US élites (see for example the World Economic Forum’s video What is the Fourth Industrial Revolution?). The notion of the Fourth Industrial Revolution clearly serves the interests of USAn élite politicans, academics and business leaders far more than it does the poor and marginalised living in remote rural areas of South Asia, or the slums of Africa.

Counter to such views are those of academics and practitioners who argue that history should be as much about the poor and underprivileged as it is about their political, military or industrial leaders. The poor have left few historical records about their lives, and yet they vastly outnumber the few élite people who have ruled and controlled them. Traditional history has been the history of the literate, designed to reinforce their positions of power, and this remains true of accounts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In 2017, Oxfam reported that eight people thus owned the same wealth as the poorest half of humanity; five of these people made most of their wealth directly from the technology sector. In an increasingly unequal world, the way to create greater equality cannot be through the use of the technologies that have created those inequalities in the first place. Rather, to change the global balance of power, there needs to be a history that focuses on the lives of the poorest and most marginalised, rather than one that glorifies élites in the interests of maintaining their hold over power.

Problem 4: male heroes of the revolution

One of the most striking and shocking features of the Huawei video that prompted this critique was that almost all of the people illustrated as the heroes of the industrial revolutions were men. Most historical accounts of industrial revolutions likewise focus on male innovators and industrialists, and yet women played a very significant part in shaping the outcomes of these technological changes, not least in their roles as workers and as mothers. Not only are accounts of industrial revolutions élite histories, they are mainly also male histories. It is thus scarcely surprising that men continue to dominate the rhetoric and imagery of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, despite the efforts of those who have sought to reveal the important role that women such as Ada Lovelace, Grace Hopper or Radia Perlman played in the origins of digital technologies (see techradar, 2018).

The perspective of a masculine revolutionary view of societal change presents significant challenges for those of us working to involve more women and girls in science and technology (see for example TEQtogether). Much more needs to be done to highlight the roles of women in history, especially histories of technology, and to encourage girls to appreciate the roles that these women have played in the past and thus the potential they have to change the future themselves (see for example, the Women’s History Review and the Journal of Women’s History). Otherwise, the masculine domination of the digital technology sector will continue to reproduce itself in ways that reproduce the gender inequalities and oppression that persist today.

Problem 5: the Fourth Industrial Revolution as a self-fulfilling prophecy

Finally, the idea of a heroic, male industrial revolution has been promoted in large part as a self fulfilling prophecy. Schwab’s book and its offspring are not so much a historical account of the past, but rather a programme for the future, in which technology will be used to make the world a better place. This is hugely problematic, because these technologies have actually been used to create significant inedqualiites in the world, and they are are continuing to do so at an ever faster rate.

The problem is that although the espoused aspirations to do good of those acclaiming the Fourth Industrial Revolution may indeed be praiseworthy, they are starting at the wrong place. The interests of those shaping these technologies are not primarily in changing the basis of our society into a fairer and more equal way of living together, but rather they are in competing to ensure their dominance and wealth as far as possible into the future. The idea of a Fourth Industrial Revolution seeks to legitimise such behaviour at all levels from that of states such as the USA, to senior leaders and investors in technology companies, to young entrepreneurs eager to make their first million. Almost all are driven primarily by their interests in money bent on the accretion of money; some are beguiled by the prestige of potential status as a hero of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In some cultures such behaviour is indeed seen as being good, but in others there are greater goods. The Fourth Industrial Revolution is in large part a conspiracy to shape the world ever more closely in the imagination of a small, rich, male and powerful élite.

Is it not time to reflect once more on the true meanings of a revolutionary idea, and to help empower some of the world’s poorest and most marginalised people to create a world that is better in their eyes rather than in our own?

[For a wider discussion of revolution, see Unwin, Tim, A revolutionary idea, in: Unwin, Tim (ed.) A European Geography, Pearson, 1998. As ever, please also note that a short post cannot include everything, so remember to read this in the broader context of my other writing, and especially Reclaiming ICT4D (OUP, 2017). For my thoughts on the other edge of the two-edged sword, do read my much shorter “Why the notion of ‘frontier technologies’ is so problematic…“]

is a global initiative committed to achieving gender equality in the digital age. Its founding partners are the

is a global initiative committed to achieving gender equality in the digital age. Its founding partners are the