I have held off writing much that is overtly critical of the UK government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, but can do so no longer. We have known for a long time that data published by governments across the world about infections is highly unreliable, although figures on deaths are somewhat more representative of reality. The UK governments’s lack of transparency, though, about its Covid-19 data is deeply worrying, and suggests deliberate deceipt. The following observations may be noted about the figures that are currently being published, and the ways in which official (and social) media use them.

I have held off writing much that is overtly critical of the UK government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, but can do so no longer. We have known for a long time that data published by governments across the world about infections is highly unreliable, although figures on deaths are somewhat more representative of reality. The UK governments’s lack of transparency, though, about its Covid-19 data is deeply worrying, and suggests deliberate deceipt. The following observations may be noted about the figures that are currently being published, and the ways in which official (and social) media use them.

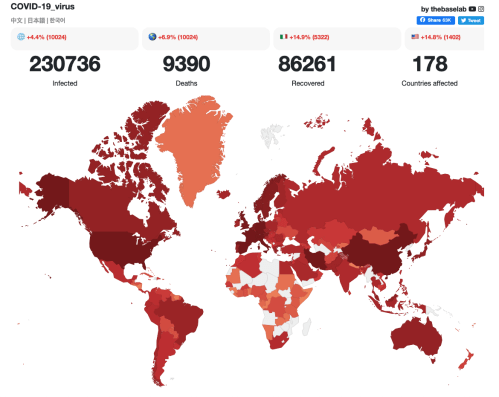

- Official infection rates are very unreliable and largely reflect the number of tests being done. These figures are so meaningless that they should be ignored in public announcements and media coverage because they give the public completely the wrong impression. Countries such as Germany are believed to be able to produce up to 500,000 tests a week (although their aim is to do 200,000 tests a day), whereas by 7th April there had only been 218,500 tests in total in the UK since the start of January. The UK government aims to achieve 100,000 tests a day by the end of April, but seems highly unlikely to meet this target; a figure of more than 10,000 tests per day in the UK was only first achieved on 1st April. The official reported number of infected cases in Germany at 119,624 on 10th April is likely to be somewhat nearer reality than the paltry 73,758 reported cases in the UK (Source: thebaselab, 10th April). In practice, it seems that most of the UK figures actually refer to those who are tested in hospital as suspected cases, since there is negligible testing of the public in general to get an idea of how extensive the spread really is. By keeping this figure apparently low, the UK government seems to be deceiving the population into believing that Covid-19 might be less extensive than in reality it is.

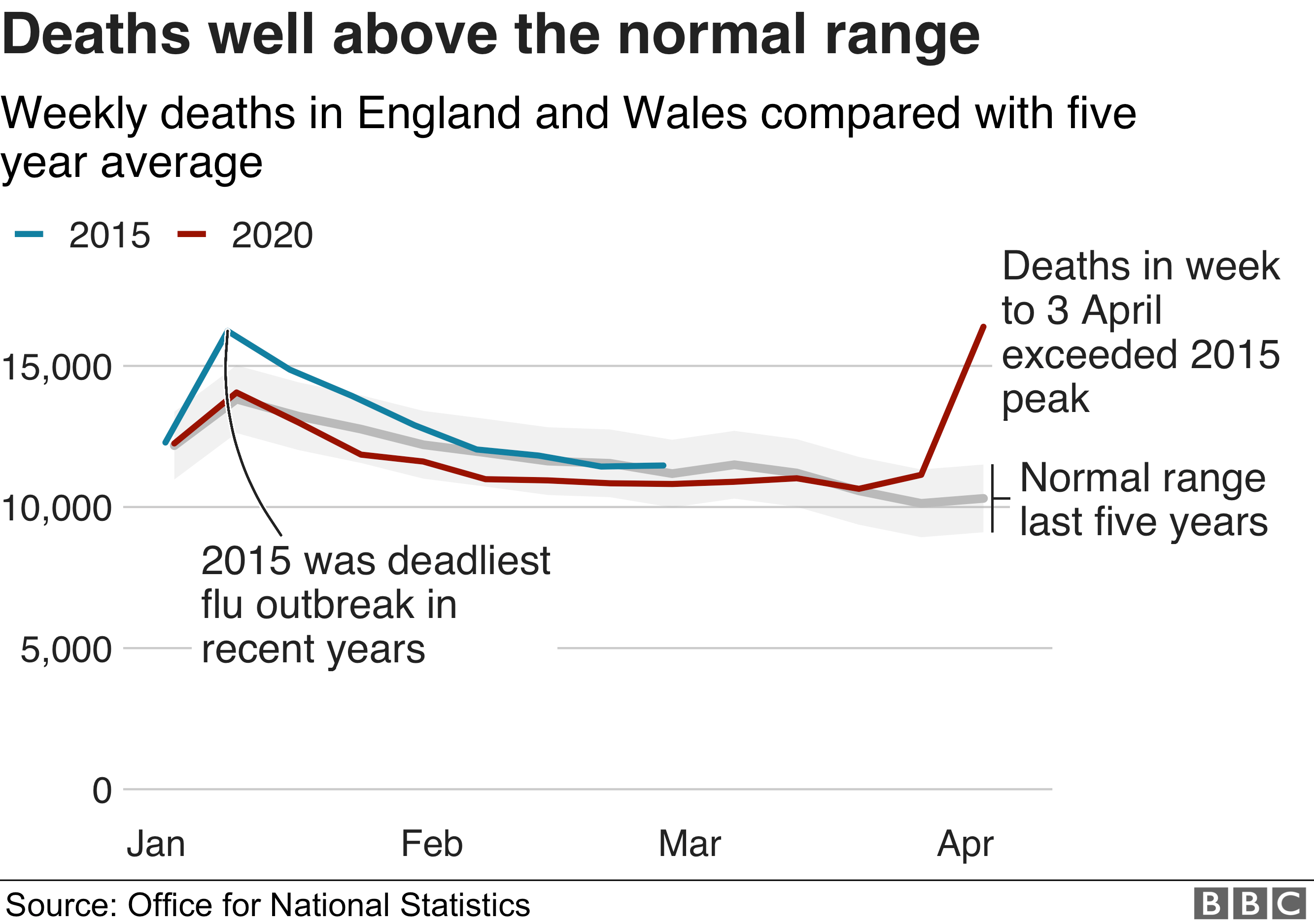

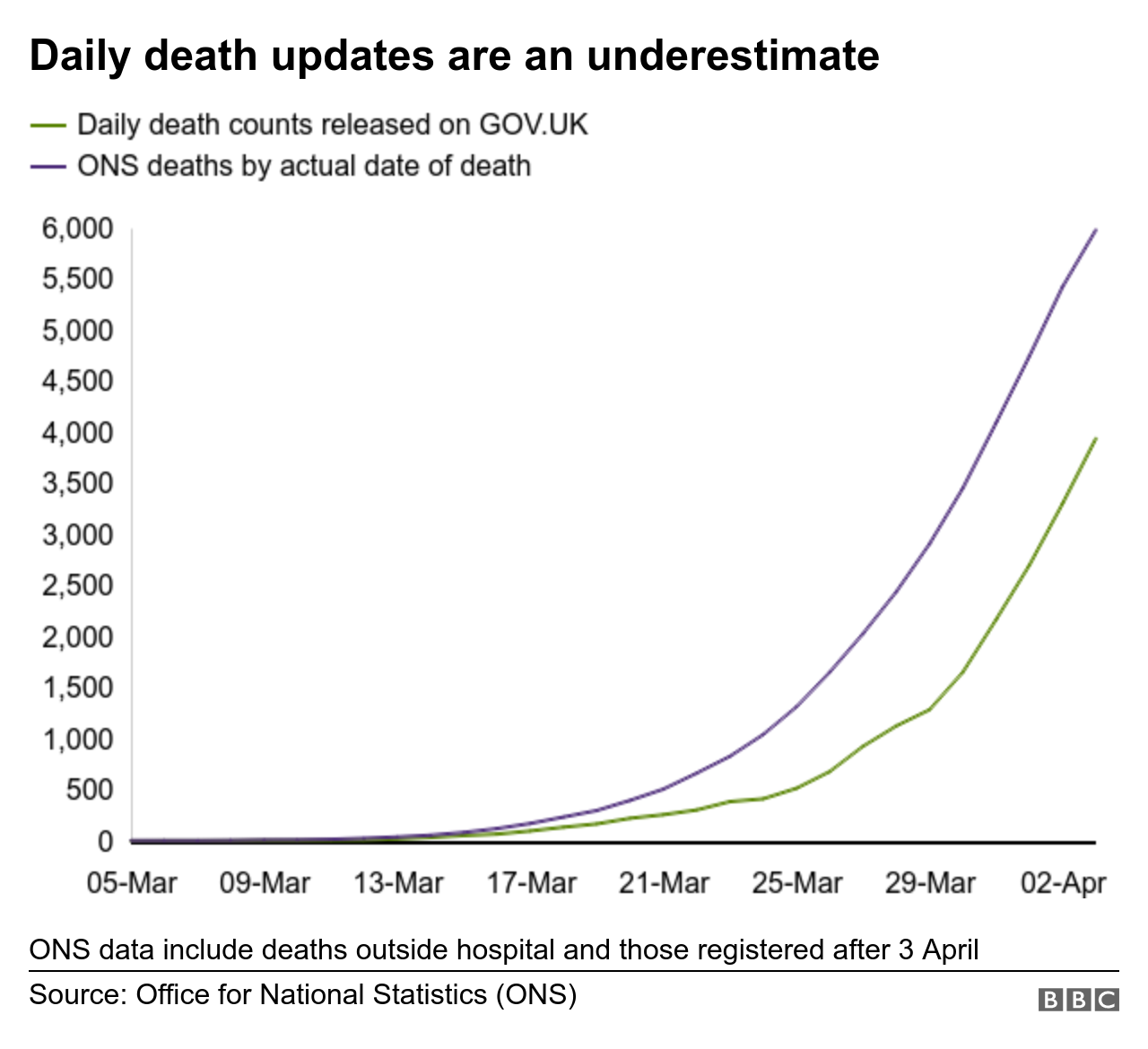

- Figures for the number of deaths should be more reliable, but are also opaque. Even with figures for deaths there is increasing cause for doubt, not least because of differences between countries reporting whether someone has died “from” or “with” Covid-19. In practice, it is even more complex than this, since some countries (such as the UK), are publishing immediate data only on those who die in hospital. Those who die in the community are only added into the total official figures at a later date. By manipulating when these figures are officially added, governments can again deceive their citizens that the deaths may in the short-term be lower than they are in reality. A good analysis of the situation in the UK has recently (8th April) been produced by Jason Oke and Carl Heneghan for The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), which highlights the considerable discrepancies between data made available by the National Health Service (NHS) and Public Health England (PHE). Not only does this make it difficult in the short-term for modellers and policy makers to know what is really happening, but it also gives a distorted picture to the public. As this report also concludes “The media should be wary of reporting daily deaths without understanding the limitations and variations in different sources”.

- Hugely unreliable mortality rates. Combining published figures for infections and deaths gives rise to figures for mortality rates. These figures are also therefore very unreliable. Because of the low levels of testing, and yet the high number of deaths in the UK (8,958; Source: thebaselab, 10th April), the UK mortality rate is reportedly the second highest in the world at 12.15%. This can be compared with Germany’s 2.18% (undoubtedly a much more accurate figure), Italy’s 12.77% (the highest in the world), and a global average of 6.06%. As I have argued previously, though, these figures are largely meaningless, and the figures that really matter are the total number of deaths divided by the total population of a country. Accordingly, to date, China has had only 0.23 deaths per 100,000 people, whereas Spain has had 33.88, Italy 30.23, France 18.80 and the UK currently 11.75 deaths per 100,000 (Source: derived from thebaselab, 10th April). Put another way, the UK figure is 51 times more than the Chinese figure. Such figures are far more meaningful than official mortality rates, and should always be used by the media (preferably using choropleth maps rather than proportional circles for total deaths).

- Extraordinarily depressing recovery rates. The UK’s current “recovery rate” is by any standards appalling. As of 9th April reported figures for the number of people who have recovered from Covid-19 in the UK were between 135 (by the baselab, and worldometers) and 351 (by Johns Hopkins University). This suggests a “recovery rate” of possibly only 0.18% in the UK (Source: thebaselab, 10th April), in contrast with China’s 94.56%, Spain’s 35.45% and a global average of 22.2%. In part this is again a result of data problems. We simply don’t know how many people have been infected mildly, and how many have survived without even knowing they have had it. It also reflects the fact that it takes time to recover, and many people are still in hospital who may yet recover. However, the UK’s figures is the worst in the world for countries where there have been more than 50 cases of Covid-19.

Such figures raise huge questions for the British government and people:

- Why are UK reported survival rates so low? Surely the government should want to do all it can to show the success of the NHS in treating patients and it should therefore publish the real figures? That is unless, of course, these figures are truly bad.

- What is the balance of numbers between those dying in hospital from Covid-19 and those leaving having recovered? The rare euphoria that greets those who leave hospital having recovered (as with 101-year-old Keith Watson who was recently discharged from a hospital in Worcestershire) suggests that very few people have actually left hospital alive having been admitted with Covid-19. Is the government trying to hide this? Is the grim truth that you are likely to die if you go into hospital with Covid-19? Does this mean that people are being admitted to hospital far too late because of the advice given by the NHS and its 111 service? Should the NHS simply stop trying to treat patients with Covid-19? (An update noted below suggests that more than half of the people going into intensive care in UK hospitals with Covid-19 die).

- Why did the government not act sooner? Some of us had argued back in January of the threat posed by the then un-named new coronavirus (I first raised concerns on 20th January, and first posted about its extent in China on social media on 27th January). It was very clear then (and not only with hindsight) that this posed a global threat. Undoubtedly the WHO failed in its warnings, and did not act quickly enough to declare a pandemic, but many governments did act to get in supplies of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), testing equipment, and ventilators. The UK government has failed its people. One quarter of my close family have probably already had Covid-19; many of my friends have also had it – some very seriously. I guess therefore that between a quarter and a third of those living in the UK may already been ill with the pandemic (Update 13th April: this must be an exaggeration, as news media over Easter suggest that experts think the current figure of infections is only 10%; Update 26th April, the MRC-IDE at Imperial College modelling back from actual deaths, suggest that only some 4.36% of the UK population is infected). They are individual human beings, and not just statistics.

These questions are hugely important now, and not just when a future review is done, because it is still not too late to act together wisely to try to limit the impact of Covid-19 in the UK. The fact that the government has not yet been transparent and open about these issues is deeply worrying. In trying to explain them the following scenarios seem likely. I very much hope they are not true, and that the government can provide clear evidence that I am wrong:

1. Throughout, the government knew that the NHS would be overwhelmed by Covid-19, and has been doing all it can to cover up its own failings and to protect the NHS. In 2016, a review called Exercise Cygnus was undertaken to simulate the impact of a major flu pandemic in the UK. The full conclusions have never been published, but sufficient evidence is in the public domain to suggest that it showed that the NHS was woefully unprepreard, with there being significant predicted shortages of intensive care beds, necessary equipment, and mortuary space. In December 2016 the then excellent Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies, conceded that “a lot of things need improving”. It is now apparent that the government (largely including people who are still leading it) did nothing to rectify the situation, and must therefore be held in part responsible for the very high death rate in the UK. Its failure to fund the NHS appropriately in recent years is but a wider symptom of this lack of care and attention to the needs of our health system. I therefore find it very depressing that this government is now so adamant in asking us to protect the NHS; as shown on the cover of the document sent to all households in the UK (illustrated above), it seems to be more concerned with protecting the NHS (listed second) above saving lives (listed third).

2. The government has consigned those least likely to survive Covid-19 to death in their homes. Despite claims that the government is caring for the most vulnerable, it seems probable that its advice to the elderly and those most at risk to stay at home was not intended primarily for their own good, but was rather to prevent the NHS from being flooded with people who were likely to die. This is callous, calculating and contemptable. On March 22nd, The Sunday Times published an article that stated that “At a private engagement at the end of February, Cummings [the Prime Minister’s Chief Advisor] outlined the government’s strategy. Those present say it was “herd immunity, protect the economy and if that means some pensioners die, too bad”. Downing Street swiftly denounced this report, but it remains widely accepted that even if these were not the exact words Cummings used, this was indeed the view of some of those at the top of the UK government at that time. Subsequent evidence would support this. Some, perhaps many, hospital trusts, for example, have clearly told their staff not to accept people who are very old and fall into the most vulnerable category. Likewise, Care Homes have been told to care for Covid-19 patients themselves, since they may not be accepted in hospital. The British Geriatrics Society thus notes (30th March) that:

- “Care homes should work with General Practitioners, community healthcare staff and community geriatricians to review Advance Care Plans as a matter of urgency with care home residents. This should include discussions about how COVID-19 may cause residents to become critically unwell, and a clear decision about whether hospital admission would be considered in this circumstance”

- “Care homes should be aware that escalation decisions to hospital will be taken in discussion with paramedics, general practitioners and other healthcare support staff. They should be aware that transfer to hospital may not be offered if it is not likely to benefit the resident and if palliative or conservative care within the home is deemed more appropriate. Care Homes should work with healthcare providers to support families and residents through this”

This policy incidentally (and also helpfully for the government) lowers the daily reporting death rate because such people are not counted as “dying in hospital”.

3. The use of digital technologies may be used to identify those unlikely to be given hospital treatment. The government quite swiftly introduced online methods by which people who think that they fall into the extremely vulnerable category could register themselves, so that they might receive help and such things as food deliveries. Whilst aspects of this can indeed be seen as positive, it also seems likely that this register could be used to deny people access to hospital services, since they are most likely to die even with hospital treatment. If true (and I hope it is not), this would be a very deeply worrying use of digital technologies. Nevertheless, care homes are being forced to hold difficult discussions with those they are meant to be caring for about end-of-life wishes, and all doctors and medical professionals are increasingly having to make complex ethical decisions about who to treat (see Tim Cook’s useful 23rd March article in The Guardian).

4. The government has tried to pass the blame onto the scientists. Early on in the crisis I was appalled to see and hear government spokespeople (including the Chief Medical Officer – so beloving of systematic reviews) saying that they were acting on scientific advice. As some of us pointed out at the time, there is no such things as unanimity in science, and so it was ridiculous for them to claim this. However, they seem to have been doing so, and in such a co-ordinated manner, because they were seeking to shift the blame in case their policies went wrong. Leading a country is a very tough job, and those who aspire to do so have to make tough decisions and stand by them. Fortunately, this position by the government is no longer tenable, especially now that academics are competing visciously in trying to prove that they are right, so that they can take the credit. Nevertheless, there remains good science and bad science, and it is frightening how many academics seem to be pandering to what governments and the public might want to hear. Tom Pike (from Imperial College), for example, predicted (against most of the prevailing evidence) in a pre-print paper with Vikas Saini on 25th March that if the UK followed China (which it clearly wasn’t doing) the total number of deaths in the UK would be around 5,700, with there being a peak of between 210 and 330 people, possibly on 3th April. Although he retracted this a few days later when it was blatantly obvious that his model was deeply flawed, news media who wanted a good news story had been very eager to publish his suggestion that the pandemic would not be as bad as others had predicted (he certainly got lots of pictures published of himself in his lab coat). Likewise, at the other end of the scale, the IHME in the USA predicted that the UK would have 66,314 deaths in total by 4th August, rising to a peak of 2,932 deaths a day on 17th April. This might have been wishful thinking, because on 7th April, UK reported deaths were only 786, which was substantially below their model prediction of around 1250. By then, though, their research had already hit the news headlines with lots of publicity. Subsequently (as at 11th April), they revised their predictions to a peak of “only” 1,674 deaths a day (estimated range 651-4,143) with a cumulated total of 37,494 deaths. These differences are very substantial, and emphasise that scientists often get it wrong. Put simply, the UK government cannot hide behind science. They can try to take the credit, but government leaders must also admit it openly when they have been wrong with the policies that they make based on the evidence.

In conclusion, by sharing these thoughts I have sought to:

- Ask the UK government to be more open and transparent in the information that it provides about Covid-19;

- Plead with media of all sorts to use data responsibly, and to be critical of claims by governments and scientists who all have their own interests in saying what they do; and

- Encourage everyone to work together for the common good, openly and honestly in trying to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Above all, I write with huge respect for the many people in our NHS who have been working in the most difficult of circumstances to try to stem the tide of Covid-19. Too many of them have already died; too many of them have become sick.

[Update 12th April: A report in The Times notes that “The death rate of Covid-19 patients admitted to intensive care now stands at more than 51 per cent, according to a study on a sample of coronavirus patients”. The original report is by ICNARC, which showed that “Of the 3883 patients, 871 patients have died, 818 patients have been discharged alive from critical care and 2194 patients were last reported as still receiving critical care”. I should add that this is despite the very valiant efforts of our NHS staff]

[Update 14th April: Great to see that the BBC is at last reporting more responsibly about government reported deaths (based on those in hospital) being a serious underestimate of total deaths, and comparing trends of deaths with previous years – two useful graphs included and copied herewith below

Thanks BBC]

Updated 14th April

One of the starkest differences between East Asian and European/North American responses to the Covid-19 pandemic has been in their differing attitudes towards face masks (used here generically, and differentiated from FFP3, also known as N95, respirators) : they are common in East Asian countries such as China, South Korea, Singapore and Japan, and yet are rarely to be seen in other parts of the world. They have been part of the package of solutions recommended in East Asia, where infection and mortality rates have generally been quite low; yet they are absent in Europe and North America where rates are much higher.

One of the starkest differences between East Asian and European/North American responses to the Covid-19 pandemic has been in their differing attitudes towards face masks (used here generically, and differentiated from FFP3, also known as N95, respirators) : they are common in East Asian countries such as China, South Korea, Singapore and Japan, and yet are rarely to be seen in other parts of the world. They have been part of the package of solutions recommended in East Asia, where infection and mortality rates have generally been quite low; yet they are absent in Europe and North America where rates are much higher. We are all going to be affected by Covid-19, and we must work together across the world if we are going to come out of the next year peacefully and coherently. The world in a year’s time will be fundamentally different from how it is now; now is the time to start planning for that future. The countries that will be most adversely affected by Covid-19 are not the rich and powerful, but those that are the weakest and that have the least developed healthcare systems. Across the world, many well-intentioned people are struggling to do what they can to make a difference in the short-term, but many of these initiatives will fail; most of them are duplicating ongoing activity elsewhere; many of them will do more harm than good.

We are all going to be affected by Covid-19, and we must work together across the world if we are going to come out of the next year peacefully and coherently. The world in a year’s time will be fundamentally different from how it is now; now is the time to start planning for that future. The countries that will be most adversely affected by Covid-19 are not the rich and powerful, but those that are the weakest and that have the least developed healthcare systems. Across the world, many well-intentioned people are struggling to do what they can to make a difference in the short-term, but many of these initiatives will fail; most of them are duplicating ongoing activity elsewhere; many of them will do more harm than good. “A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and

“A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and

It is much easier to enjoy change if you treat it in a positive way. Think about all the good things: no need to travel to work; spending time with those you love (hopefully); doing things at home that you have always wanted to! Treat the next few weeks or months as an opportunity to do new and exciting things. Discover your home again! (Although this highlights the huge challenges facing the homeless).

It is much easier to enjoy change if you treat it in a positive way. Think about all the good things: no need to travel to work; spending time with those you love (hopefully); doing things at home that you have always wanted to! Treat the next few weeks or months as an opportunity to do new and exciting things. Discover your home again! (Although this highlights the huge challenges facing the homeless). If at all possible, it is absolutely essential to have separate sleeping and working places so that you remain sane. There is much evidence that trying to sleep in the same place in which you work can confuse the mind, and may tend to make it continue to work when you want to go to sleep – even subconsciously – rather than enabling you to rest. You are likely to be worried about the implications of Covid-19, and so it is essential that you do all you can to ensure a good night’s sleep. This may not be easy for many people, but you should still try not to work in your bedroom! And don’t continue working too late – give your body the time it needs to relax and rest.

If at all possible, it is absolutely essential to have separate sleeping and working places so that you remain sane. There is much evidence that trying to sleep in the same place in which you work can confuse the mind, and may tend to make it continue to work when you want to go to sleep – even subconsciously – rather than enabling you to rest. You are likely to be worried about the implications of Covid-19, and so it is essential that you do all you can to ensure a good night’s sleep. This may not be easy for many people, but you should still try not to work in your bedroom! And don’t continue working too late – give your body the time it needs to relax and rest. It is incredibly easy to put on weight when working at home, even if you think you are not doing so! This is bad for your health, and bad for morale. It’s easy to understand why this happens: many people commute to work, and even if not cycling, they walk from their transport node to their office; homes are smaller than offices, and so you generally walk more at work than at home; and often you will go out of the office during the daytime, perhaps for lunch, but you can’t do this if you are self-isolating. There are lots of things, though, that you can do to rectify this: walk up and down stairs several times a day (never take the lift); ensure that you go for a short walk every hour (even if it is just 20 times around your home); if you have some outdoor space, take up gardening (it uses lots of muscles you never thought you had!); and even if you don’t decide to buy a stationary bike (actually much cheaper than joining a gym), you can still exercise with a resistance band, or even use bags of sugar as weights!

It is incredibly easy to put on weight when working at home, even if you think you are not doing so! This is bad for your health, and bad for morale. It’s easy to understand why this happens: many people commute to work, and even if not cycling, they walk from their transport node to their office; homes are smaller than offices, and so you generally walk more at work than at home; and often you will go out of the office during the daytime, perhaps for lunch, but you can’t do this if you are self-isolating. There are lots of things, though, that you can do to rectify this: walk up and down stairs several times a day (never take the lift); ensure that you go for a short walk every hour (even if it is just 20 times around your home); if you have some outdoor space, take up gardening (it uses lots of muscles you never thought you had!); and even if you don’t decide to buy a stationary bike (actually much cheaper than joining a gym), you can still exercise with a resistance band, or even use bags of sugar as weights!

When you don’t have to catch public transport, or cycle/drive/walk to work it is terribly easy to be lazy, and let time slip by without focusing on the tasks in hand. Most people like to feel they have achieved something positive every day. One way to ensure this is to plan each day carefully. And don’t forget to give yourself treats when you have achieved something – whatever it is that you enjoy!

When you don’t have to catch public transport, or cycle/drive/walk to work it is terribly easy to be lazy, and let time slip by without focusing on the tasks in hand. Most people like to feel they have achieved something positive every day. One way to ensure this is to plan each day carefully. And don’t forget to give yourself treats when you have achieved something – whatever it is that you enjoy! This is closely linked to planning – but don’t just spend all your time relaxing, or doing nothing but work! It’s important to maintain diversity in life. If your boss expects you to work a 10 hour day, then make sure that you do (hopefully s/he won’t). But even then you have 14 hours each day to do other things (please try and get 7 hours of sleep – it will help to keep you fit and well)! I find that having a colour coded diary with a clear schedule helps me manage my life – even though I tend to work far too much! The trouble is I enjoy my work!

This is closely linked to planning – but don’t just spend all your time relaxing, or doing nothing but work! It’s important to maintain diversity in life. If your boss expects you to work a 10 hour day, then make sure that you do (hopefully s/he won’t). But even then you have 14 hours each day to do other things (please try and get 7 hours of sleep – it will help to keep you fit and well)! I find that having a colour coded diary with a clear schedule helps me manage my life – even though I tend to work far too much! The trouble is I enjoy my work! Many people who now have to work at home because of Covid-19 will not have had much experience previously at doing this. It can come as a shock getting to see other aspects of a loved one’s life. Tensions are bound to arise, especially if you are trying to work when your children are at home because school has been closed. It can help to have a thorough and transparent discussion between all members of a household (including the children) to set some ground rules for how you are going to manage the next few weeks and months. This can indeed be challenging, and will frequently require revisiting, but having some shared expectations can help reduce the tensions that are bound to arise. Listening (however difficult it is) often helps to lower tension.

Many people who now have to work at home because of Covid-19 will not have had much experience previously at doing this. It can come as a shock getting to see other aspects of a loved one’s life. Tensions are bound to arise, especially if you are trying to work when your children are at home because school has been closed. It can help to have a thorough and transparent discussion between all members of a household (including the children) to set some ground rules for how you are going to manage the next few weeks and months. This can indeed be challenging, and will frequently require revisiting, but having some shared expectations can help reduce the tensions that are bound to arise. Listening (however difficult it is) often helps to lower tension. The clothes we wear represent how we feel, but can also help shape those feelings. It is amazing what an effect it can have if you get dressed smartly when you are feeling low. Likewise, most people like to dress in more relaxed clothing when they stop working, and we don’t usually sleep in the same clothes that we have worn during the day. Just because you are working at home, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will work well in your pyjamas (and imagine if you are suddenly asked to join a conference call without time to change!). The simple message is that we should continue to take care of ourselves, just as if we were going out to work or to a party!

The clothes we wear represent how we feel, but can also help shape those feelings. It is amazing what an effect it can have if you get dressed smartly when you are feeling low. Likewise, most people like to dress in more relaxed clothing when they stop working, and we don’t usually sleep in the same clothes that we have worn during the day. Just because you are working at home, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will work well in your pyjamas (and imagine if you are suddenly asked to join a conference call without time to change!). The simple message is that we should continue to take care of ourselves, just as if we were going out to work or to a party! Enjoy the physicality of life. Don’t always feel you have to be online in case “work” wants to get in touch. None of us are that important. The world will get by perfectly well without us! There is a lot of evidence that being online late at night can also disturb our sleep patterns. Remember that although we are increasingly being programmed to believe that digital technology gives us much more freedom in how we work, it is actually mainly used by the owners of capital further to exploit their workforces by making them work longer hours for no extra pay!

Enjoy the physicality of life. Don’t always feel you have to be online in case “work” wants to get in touch. None of us are that important. The world will get by perfectly well without us! There is a lot of evidence that being online late at night can also disturb our sleep patterns. Remember that although we are increasingly being programmed to believe that digital technology gives us much more freedom in how we work, it is actually mainly used by the owners of capital further to exploit their workforces by making them work longer hours for no extra pay! Being self-isolated at home will mean that you have vastly more time on your hands than you can ever imagine (as long as you don’t work all day and night). Use it creatively to do something that you have always thought about doing, but never had the time before. Read those books that you always wanted to. Learn a musical instrument. Learn to speak a new language (Python or Mandarin). Take up painting. Discover how to cook delicious meals with limited resources. Photograph the wildlife in your garden. Grow your own vegetables. Make beer. Even just plan your next (or first) holiday.

Being self-isolated at home will mean that you have vastly more time on your hands than you can ever imagine (as long as you don’t work all day and night). Use it creatively to do something that you have always thought about doing, but never had the time before. Read those books that you always wanted to. Learn a musical instrument. Learn to speak a new language (Python or Mandarin). Take up painting. Discover how to cook delicious meals with limited resources. Photograph the wildlife in your garden. Grow your own vegetables. Make beer. Even just plan your next (or first) holiday.