Now is the time to be thinking seriously about the kind of world that we wish to live in once Covid-19 has finished its rampage across Europe and North America.[i] Although its potential direct health impact in Africa and South Asia remains uncertain at the time of writing, countries within these continents have already seen dramatic disruption and much hardship as well as numerous deaths having been caused by the measures introduced by governments to restrict its spread. It is already clear that it is the poorest and most marginalised who suffer most, as witnessed, for example, by the impact of Modi’s lockdown in India on migrant workers.[ii]

This post highlights five likely global impacts that will be hastened by Covid-19, and argues that we need to use this disruption constructively to shape a better world in the future, rather than succumb to the potential and substantial damage that will be caused, especially to the lives of the world’s poorest and most marginalised. It may be that for many countries in the world, the impact of Covid-19 will be even more significant than was the impact of the 1939-45 war. Digital technologies are above all accelerators, and most of those leading the world’s major global corporations are already taking full advantage of Covid-19 to increase their reach and their profits.[iii]

The inexorable rise of China and the demise of the USA

Source: Hiram1555.com

I have written previously about the waxing of China and the waning of the USA; China is the global political-economic powerhouse of the present, not just of the future.[iv] One very significant impact of Covid-19 will be to increase the speed of this major shift in global power. Just as 1945 saw the beginning of the final end of the British Empire, so 2020 is likely to see the beginning of the end of the USA as the dominant global (imperial) power. Already, even in influential USAn publications, there is now much more frequent support for the view that the US is a failing state.[v] This transition is likely to be painful, and it will require world leaders of great wisdom to ensure that it is less violent than may well be the case.

The differences between the ways in which the USA and China have responded to Covid-19 have been marked, and have very significant implications for the political, social and economic futures of these states. Whilst little trust should be placed on the precise accuracy of reported Covid-19 mortality rate figures throughout the world, China has so far reported a loss of 3.2 people per million to the disease (as of 17 April, and thus including the 1290 uplift announced that day), whereas the USA has reported deaths of 8.38 per 100,000 (as of that date); moreover, China’s figures seem to have stabilised, whereas those for the USA continue to increase rapidly.[vi] These differences are not only very significant in human terms, but they also reflect a fundamental challenge in the relative significance of the individual and the community in US and Chinese society.

Few apart from hardline Republicans in the USA now doubt the failure of the Trump regime politically, socially, economically and culturally. This has been exacerbated by the US government’s failure to manage Covid-19 effectively (even worse than the UK government’s performance), and its insistent antagonism towards China through its deeply problematic trade-war[vii] even before the outbreak of the present coronavirus. Anti-Chinese rhetoric in the USA is but a symptom of the realisation of the country’s fundamental economic and policial weaknesses in the 21st century. President Trump’s persistent use of the term “Chinese virus” instead of Covid-19[viii] is also just a symptom of a far deeper malaise. Trump is sadly not the problem; the problem is the people and system that enabled him to come to power and in whose interests he is trying to serve (alongside his own). China seems likely to come out of the Covid-19 crisis much stronger than will the USA.[ix]

Whether people like it or not, and despite cries from the western bourgeoisie that it is unfair, and that the Chinese have lied about the extent of Covid-19 in their own country in its early stages, this is the reality. China is the dominant world power today, let alone tomorrow.

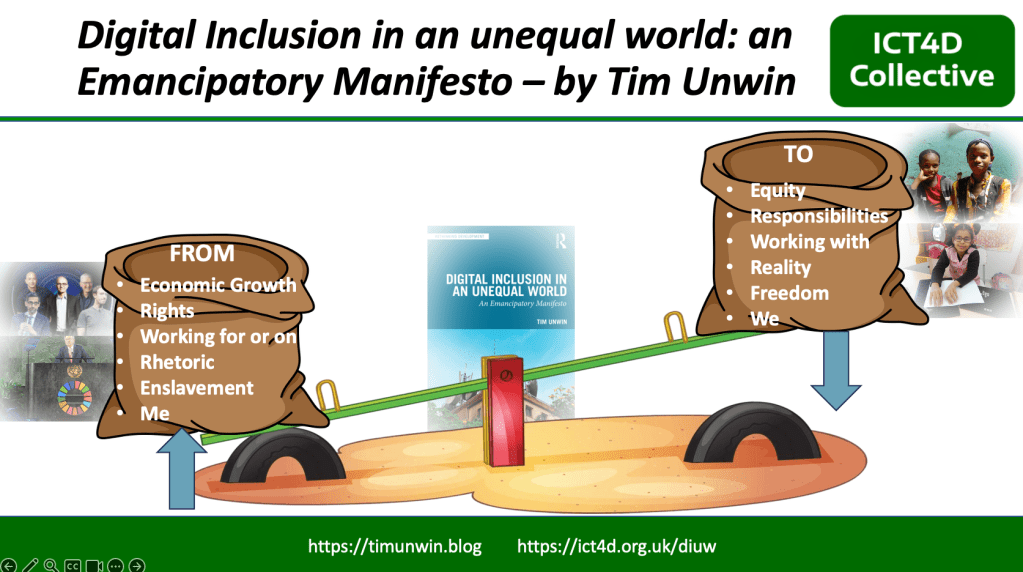

An ever more digital world

Source: Forbes.com

The digital technology sector is already the biggest winner from Covid-19. Everyone with access, knowledge and ability to pay for connectivity and digital devices has turned to digital technologies to continue with their work, maintain social contacts, and find entertainment during the lockdowns that have covered about one-third of the world’s population by mid-April.[x] Those who previously rarely used such technologies, have overnight been forced to use them for everything from buying food online, to maintaining contacts with relatives and friends.

There is little evidence that the tech sector was prepared for such a windfall in the latter part of 2019,[xi] but major corporations and start-ups alike have all sought to exploit its benefits as quickly as possible in the first few months of 2020, as testified by the plethora of announcements claiming how various technologies can win the fight against Covid-19.[xii]

One particularly problematic outcome has been the way in which digital tech champions and activists have all sought to develop new solutions to combat Covid-19. While sometimes this is indeed well intended, more often than not it is primarily so that they can benefit from funding that is made available for such activities by governments and donors, or primarily to raise the individual or corporate profile of those involved. For them, Covid-19 is a wonderful business opportunity. Sadly, many such initiatives will fail to deliver appropriate solutions, will be implemented after Covid-19 has dissipated, and on some occasions will even do more harm than good.[xiii]

There are many paradoxes and tensions in this dramatically increased role of digital technology after Covid-19. Two are of particular interest. First, many people who are self-isolating or social distancing are beginning to crave real, physical human contact, and are realising that communicating only over the Internet is insufficiently fulfilling. This might offer some hope for the future of those who still believe in the importance of non-digitally mediated human interaction, although I suspect that such concerns may only temporarily delay our demise into a world of cyborgs.[xiv] Second, despite the ultimate decline in the US economy and political power noted above, US corporations have been very well placed to benefit from the immediate impact of Covid-19, featuring in prominent initiatives such as UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition,[xv] or the coalition of pharmaceutical companies brought together by the Gates Foundation.[xvi]

Whatever the precise details, it is an absolute certainty that the dominance of digital technologies in everyone’s lives will increase very dramatically following Covid-19 and this will be exploited by those intent on reaping the profits from such expansion in their own interests.

Increasing acceptance of surveillance by states and companies: the end of privacy as we know it.

Source: Wired.com

A third, related, global impact of Covid-19 will be widely increased global acceptance of the roles of states and companies in digital surveillance. Already, before 2020, there was a growing, albeit insufficient, debate about the ethics of digital surveillance by states over issues such as crime and “terrorism”, and its implications for privacy.[xvii] However, some states, such as China, South Korea, Singapore and Israel, have already used digital technologies and big data analytics extensively and apparently successfully in monitoring and tracking the spread of Covid-19,[xviii] and other coalitions of states and the private sector are planning to encourage citizens to sign up to having fundamental aspects of what has previously been considered to be their private and personal health information made available to unknown others.[xix]

One problem with such technologies is that they require substantial numbers of people to sign up to and then use them. In more authoritarian states where governments can make such adherence obligatory by imposing severe penalties for failure to do so, they do indeed appear to be able to contribute to reduction in the spread of Covid-19 in the interests of the wider community. However, in more liberal democratic societies, which place the individual about the community in importance, it seems less likely that they will be acceptable.

Despite such concerns, the growing evidence promoted by the companies that are developing them that such digital technologies can indeed contribute to enhanced public health will serve as an important factor in breaking down public resistance to the use of surveillance technologies and big data analytics. Once again, this will ultimately serve the interest of those who already have greater political and economic power than it will the interests of the most marginalised.

Online shopping and the redesign of urban centres.

Source: Independent.co.uk

Self-isolation and social distancing have led to the dramatic emptying of towns and cities across the world. Businesses that have been unable to adapt to online trading have overnight been pushed into a critical survival situation, with governments in many of the richer countries of the world being “forced” to offer them financial bail-outs to help them weather the storm. Unfortunately, most of this money is going to be completely wasted and will merely create huge national debts for years into the future. People who rarely before used online shopping are now doing so because they believe that no other method of purchasing goods is truly safe.

The new reality will be that most people will have become so used to online shopping that they are unlikely to return in the future to traditional shopping outlets. Companies that have been unable to adjust to the new reality will fail. The character of our inner-city areas will change beyond recognition. This is a huge opportunity for the re-design of urban areas in creative, safe and innovative ways. Already, the environmental impact of a reduction in transport and pollution has been widely seen; wildlife is enjoying a bonanza; people are realising that their old working and socialising patterns may not have been as good as they once thought.[xx] Unfortunately, it is likely that this opportunity may not be fully grasped, and instead governments that lack leadership and vision will instead seek to prop up backward-looking institutions, companies and organisations, intent on preserving infrastructure and economic activities that are unfit for purpose in the post-pandemic world. Such a mentality will lead to urban decay and ghettoization, where people will fear to tread, and there is a real danger of a downward spiral of urban deprivation.

There are, though, many bright signs of innovation and creativity for those willing to do things differently. Shops and restaurants that have been able to find efficient trustworthy drivers are now offering new delivery services; students are able to draw on the plethora of online courses now available; new forms of communal activity are flourishing; and most companies are realising that they don’t actually need to spend money on huge office spaces, but can exploit their labour even more effectively by enabling them to work from home.

We must see the changes brought about by responses to Covid-19 as important opportunities to build for the future, and to create human-centred urban places that are also sensitive to the natural environments in which they are located.

Increasing global inequalities

Source: Gulfnews.com

The net outcome of the above four trends will lead inexorably to a fifth, and deeply concerning issue: the world will become an even more unequal place, where those who can adapt and survive will flourish, but where the most vulnerable and marginalised will become even more immiserated.

This is already all too visible. Migrant workers are being ostracised, and further marginalised.[xxi] In India, tens of thousands of labourers are reported to have left the cities, many of them walking home hundreds of kilometres to their villages.[xxii] In China, Africans are reported as being subjected to racist prejudice, being refused service in shops and evicted from their residences.[xxiii] In the UK, many food banks have had to close and it is reported that about 1.5. million people a day are going without food.[xxiv] The World Bank is reporting that an extra 40-50 million people across the world will be forced into poverty by Covid-19, especially in Africa.[xxv] People with disabilities have become even more forgotten and isolated.[xxvi] The list of immediate crises grows by the day.

More worrying still is that there is no certainty that these short-term impacts will immediately bounce-back once the pandemic has passed. It seems at least as likely that many of the changes will have become so entrenched that aspects of living under Covid-19 will become the new norm. Once again, those able to benefit from the changes will flourish, but the uneducated, those with disabilities, the ethnic minorities, people living in isolated areas, refugees, and women in patriarchal societies are all likely to find life much tougher in 2021 and 2022 even than they do at present. Much of this rising inequality is being caused, as noted above, by the increasing role that digital technologies are playing in people’s lives. Those who have access and can afford to use the Internet can use it for shopping, employment, entertainment, learning, and indeed most aspects of their lives. Yet only 59% of the world’s population are active Internet users.[xxvii]

Looking positively to the future.

People will respond in different ways to these likely trends over the next few years, but we will all need to learn to live together in a world where:

- China is the global political economic power,

- Our lives will become ever more rapidly experienced and mediated through digital technology,

- Our traditional views of privacy are replaced by a world of surveillance,

- Our towns and cities have completely different functions and designs, and

- There is very much greater inequality in terms of opportunities and life experiences.

In dealing with these changes, it is essential to remain positive; to see Covid-19 as an opportunity to make the world a better place for everyone to live in, rather than just as a threat of further pain, misery and death, or an opportunity for a few to gain unexpected windfall opportunities to become even richer. Six elements would seem to be important in seeking to ensure that as many people as possible can indeed flourish once the immediate Covid-19 pandemic has dissipated:

- First, these predictions should encourage all of us to prioritise more on enhancing the lives of the poorest and the most marginalised, than on ensuring economic growth that mainly benefits the rich and privileged. This applies at all scales, from designing national health and education services, to providing local, community level care provision.

- This requires an increased focus on negotiating communal oriented initiatives and activities rather than letting the greed and selfishness of individualism continue to rule the roost.

- Third, it is essential that we use this as an opportunity to regain our physical sentient humanity, and reject the aspirations of those who wish to create a world that is only experienced and mediated through digital technology. We need to regain our very real experiences of each other and the world in which we live through our tastes, smells, the sounds we hear, the touches we feel, and the sights we see.

- Fourth, it seems incredibly important that we create a new global political order safely to manage a world in which China replaces the USA as the dominant global power. The emergence of new political counterbalances, at a regional level as with Europe, South Asia, Africa and Latin America seems to be a very important objective that remains to be realised. Small states that choose to remain isolated, however arrogant they are about the “Great”ness of their country, will become ever more vulnerable to the vagaries of economic, political and demographic crisis.

- Fifth, we need to capitalise on the environmental impact of Covid-19 rapidly to shape a world of which we are but a part, and in which we care for and co-operate with the rich diversity of plant and animal life that enjoys the physical richness of our planet. This will require a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the harm caused to our world by the design and use of digital technologies.[xxviii]

- Finally, we need to agree communally on the extent to which individual privacy matters, and whether we are happy to live in a world of omnipresent surveillance by companies (enabling them to reap huge profits from our selves as data) and governments (to maintain their positions of power, authority and dominance). This must not be imposed on us by powerful others. It is of paramount importance that there is widespread informed public and communal discussion about the future of surveillance in a post-Covid-19 era.

I trust that these comments will serve to provoke and challenge much accepted dogma and practice. Above all, let’s try to think of others more than we do ourselves, let’s promote the reduction of inequality over increases in economic growth, and let’s enjoy an integral, real and care-filled engagement with the non-human natural world.

Notes:

[i] For current figures see https://coronavirus.thebaselab.com/ and https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6, although all data related with this coronavirus must be treated with great caution; see https://unwin.wordpress.com/2020/04/11/data-and-the-scandal-of-the-uks-covid-19-survival-rate/

[ii] Modi’s hasty coronavirus lockdown of India leaves many fearful for what comes next, https://time.com/5812394/india-coronavirus-lockdown-modi/

[iii] Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter and Square, might well be an exception with his $1 billion donation to support Covid-19 relief and other charities; see https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/7/21212766/jack-dorsey-coronavirus-covid-19-donate-relief-fund-square-twitter

[iv] See, for example, discussion in Unwin, T. (2017) Reclaiming ICT4D, Oxford: Oxford University Press. I appreciate that such arguments infuriate many people living in the USA,

[v] See, for example, George Parker’s, We Are Living in a Failed State: The coronavirus didn’t break America. It revealed what was already broken, The Atlantic, June 2020 (preview) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/underlying-conditions/610261/.

[vi] Based on figures from https://coronavirus.thebaselab.com/ on 15th April 2020. For comparison, Spain had 39.74 reported deaths per 100,000, Italy 35.80, and the UK 18.96.

[vii] There are many commentaries on this, but The Wall Street Journal’s account on 9 February 2020 https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-china-trade-war-reshaped-global-commerce-11581244201 is useful, as is the Pietersen Institute’s timeline https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/trump-trade-war-china-date-guide.

[viii] For a good account of his use of language see Eren Orbey’s comment in The New Yorker, Trump’s “Chinese virus” and what’s at stake in the coronovirus’s name, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/whats-at-stake-in-a-viruss-name

[ix] China’s massive long-term strategic investments across the world, not least through its 一带一路 (Belt and Road) initiative, have placed it in an extremely strong position to reap the benefits of its revitalised economy from 2021 onwards (for a good summary of this initiative written in January 2020 see https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative)

[x] Kaplan, J., Frias, L. and McFall-Johnsen, M., A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown…, https://www.businessinsider.com/countries-on-lockdown-coronavirus-italy-2020-3?r=DE&IR=T

[xi] This is despite conspiracy theorists arguing that those who were going to gain most from Covid-19 especially in the digital tech and pharmaceutical industry had been active in promoting global fear of the coronavirus, or worse still had actually engineered it for their advantage. See, for example, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/technology/bill-gates-virus-conspiracy-theories.html, or Thomas Ricker, Bill Gates is now the leading target for Coronavirus falsehoods, says report, https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/17/21224728/bill-gates-coronavirus-lies-5g-covid-19 .

[xii] See, for example, Shah, H. and Kumar, K., Ten digital technologies helping humans in the fight against Covid-19, Frost and Sullivan, https://ww2.frost.com/frost-perspectives/ten-digital-technologies-helping-humans-in-the-fight-against-covid-19/, Gergios Petropolous, Artificial interlligence in the fight against COVID-19, Bruegel, https://www.bruegel.org/2020/03/artificial-intelligence-in-the-fight-against-covid-19/, or Beech, P., These new gadgets were designed to fight COVID-19, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-covid19-pandemic-gadgets-innovation-technology/. It is also important to note that the notion of “fighting” the coronavirus is also deeply problematic.

[xiii] For my much more detailed analysis of these issues, see Tim Unwin (26 March 2020), collaboration-and-competition-in-covid-19-response, https://unwin.wordpress.com/2020/03/26/collaboration-and-competition-in-covid-19-response/

[xiv] For more on this see Tim Unwin (2017) Reclaiming ICT4D, Oxford: Oxford University Press, and for a brief comment https://unwin.wordpress.com/2016/08/03/dehumanization-cyborgs-and-the-internet-of-things/.

[xv] Although, significantly, Chinese companies are also involved; see https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition

[xvi] For the work of the Gates Foundation and US pharmaceutical companies in fighting Covid-19 https://www.outsourcing-pharma.com/Article/2020/03/27/Bill-Gates-big-pharma-collaborate-on-COVID-19-treatments

[xvii] There is a huge literature, both academic and policy related, on this, but see for example OCHCR (2014) Online mass-surveillance: “Protect right to privacy even when countering terrorism” – UN expert, https://www.ohchr.org/SP/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=15200&LangID=E; Privacy International, Scrutinising the global counter-terrorism agenda, https://privacyinternational.org/campaigns/scrutinising-global-counter-terrorism-agenda; Simon Hale-Ross (2018) Digital Privacy, Terrorism and Law Enforcement: the UK’s Response to Terrorist Communication, London: Routledge; and Lomas, N. (2020) Mass surveillance for national security does conflict with EU privacy rights, court advisor suggests, TechCrunch, https://techcrunch.com/2020/01/15/mass-surveillance-for-national-security-does-conflict-with-eu-privacy-rights-court-advisor-suggests/.

[xviii] Kharpal, A. (26 March 2020) Use of surveillance to fight coronavirus raised c oncenrs about government power after pandemic ends, CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/27/coronavirus-surveillance-used-by-governments-to-fight-pandemic-privacy-concerns.html; but see also more critical comments about the efficacy of such systems as by Vaughan, A. (17 April 2020) There are many reasons why Covid-19 contact-tracing apps may not work, NewScientist, https://www.newscientist.com/article/2241041-there-are-many-reasons-why-covid-19-contact-tracing-apps-may-not-work/

[xix] There are widely differing views as to the ethics of this. See, for example, Article 19 (2 April 2020) Coronavirus: states use of digital surveillance technologies to fight pandemic must respect human rights, https://www.article19.org/resources/covid-19-states-use-of-digital-surveillance-technologies-to-fight-pandemic-must-respect-human-rights/ ; McDonald, S. (30 March 2020) The digital response to the outbreak of Covid-19, https://www.cigionline.org/articles/digital-response-outbreak-covid-19. See also useful piece by Arcila (2020) for ICT4Peace on “A human-centric framework to evaluate the risks raised by contact-tracing applications” https://mcusercontent.com/e58ea7be12fb998fa30bac7ac/files/07a9cd66-0689-44ff-8c4f-6251508e1e48/Beatriz_Botero_A_Human_Rights_Centric_Framework_to_Evaluate_the_Security_Risks_Raised_by_Contact_Tracing_Applications_FINAL_BUA_6.pdf.pdf

[xx] See, for example, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200326-covid-19-the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-the-environment, https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/world/the-environmental-impact-of-covid-19/ss-BB11JxGv?li=BBoPWjQ, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/26/life-after-coronavirus-pandemic-change-world, and https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-the-coronavirus-pandemic-is-affecting-co2-emissions/.

[xxi] See The Guardian (23 April 2020) ‘We’re in a prison’: Singapore’s million migrant workers suffer as Covid-19 surges back, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/singapore-million-migrant-workers-suffer-as-covid-19-surges-back

[xxii] Al Jazeera (6 April 2020) India: Coronavirus lockdown sees exodus from cities, https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/newsfeed/2020/04/india-coronavirus-lockdown-sees-exodus-cities-200406104405477.html.

[xxiii] Financial Times (13th April) China-Africa relations rocked by alleged racism over Covid-19, https://www.ft.com/content/48f199b0-9054-4ab6-aaad-a326163c9285

[xxiv] Global Citizen (22 April 2020) Covid-19 Lockdowns are sparking a hunger crisis in the UK, https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/covid-19-food-poverty-rising-in-uk/

[xxv] Mahler, D.G., Lakner, C., Aguilar, R.A.C. and Wu, H. (20 April 2020) The impact of Covid-19 (Coronavirus) on global poverty: why Sub-Saharan Africa might be the region hardest hit, World Bank Blogs, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/impact-covid-19-coronavirus-global-poverty-why-sub-saharan-africa-might-be-region-hardest

[xxvi] Bridging the Gap (2020) The impact of Covid-19 on persons with disabilities, https://bridgingthegap-project.eu/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-with-disabilities/

[xxvii] Statista (Januarv 2020) https://www.statista.com/statistics/269329/penetration-rate-of-the-internet-by-region/

[xxviii] For a wider discussion of the negative environmental impacts of climate change see https://unwin.wordpress.com/2020/01/16/digital-technologies-and-climate-change/.

It is much easier to enjoy change if you treat it in a positive way. Think about all the good things: no need to travel to work; spending time with those you love (hopefully); doing things at home that you have always wanted to! Treat the next few weeks or months as an opportunity to do new and exciting things. Discover your home again! (Although this highlights the huge challenges facing the homeless).

It is much easier to enjoy change if you treat it in a positive way. Think about all the good things: no need to travel to work; spending time with those you love (hopefully); doing things at home that you have always wanted to! Treat the next few weeks or months as an opportunity to do new and exciting things. Discover your home again! (Although this highlights the huge challenges facing the homeless). If at all possible, it is absolutely essential to have separate sleeping and working places so that you remain sane. There is much evidence that trying to sleep in the same place in which you work can confuse the mind, and may tend to make it continue to work when you want to go to sleep – even subconsciously – rather than enabling you to rest. You are likely to be worried about the implications of Covid-19, and so it is essential that you do all you can to ensure a good night’s sleep. This may not be easy for many people, but you should still try not to work in your bedroom! And don’t continue working too late – give your body the time it needs to relax and rest.

If at all possible, it is absolutely essential to have separate sleeping and working places so that you remain sane. There is much evidence that trying to sleep in the same place in which you work can confuse the mind, and may tend to make it continue to work when you want to go to sleep – even subconsciously – rather than enabling you to rest. You are likely to be worried about the implications of Covid-19, and so it is essential that you do all you can to ensure a good night’s sleep. This may not be easy for many people, but you should still try not to work in your bedroom! And don’t continue working too late – give your body the time it needs to relax and rest. It is incredibly easy to put on weight when working at home, even if you think you are not doing so! This is bad for your health, and bad for morale. It’s easy to understand why this happens: many people commute to work, and even if not cycling, they walk from their transport node to their office; homes are smaller than offices, and so you generally walk more at work than at home; and often you will go out of the office during the daytime, perhaps for lunch, but you can’t do this if you are self-isolating. There are lots of things, though, that you can do to rectify this: walk up and down stairs several times a day (never take the lift); ensure that you go for a short walk every hour (even if it is just 20 times around your home); if you have some outdoor space, take up gardening (it uses lots of muscles you never thought you had!); and even if you don’t decide to buy a stationary bike (actually much cheaper than joining a gym), you can still exercise with a resistance band, or even use bags of sugar as weights!

It is incredibly easy to put on weight when working at home, even if you think you are not doing so! This is bad for your health, and bad for morale. It’s easy to understand why this happens: many people commute to work, and even if not cycling, they walk from their transport node to their office; homes are smaller than offices, and so you generally walk more at work than at home; and often you will go out of the office during the daytime, perhaps for lunch, but you can’t do this if you are self-isolating. There are lots of things, though, that you can do to rectify this: walk up and down stairs several times a day (never take the lift); ensure that you go for a short walk every hour (even if it is just 20 times around your home); if you have some outdoor space, take up gardening (it uses lots of muscles you never thought you had!); and even if you don’t decide to buy a stationary bike (actually much cheaper than joining a gym), you can still exercise with a resistance band, or even use bags of sugar as weights!

When you don’t have to catch public transport, or cycle/drive/walk to work it is terribly easy to be lazy, and let time slip by without focusing on the tasks in hand. Most people like to feel they have achieved something positive every day. One way to ensure this is to plan each day carefully. And don’t forget to give yourself treats when you have achieved something – whatever it is that you enjoy!

When you don’t have to catch public transport, or cycle/drive/walk to work it is terribly easy to be lazy, and let time slip by without focusing on the tasks in hand. Most people like to feel they have achieved something positive every day. One way to ensure this is to plan each day carefully. And don’t forget to give yourself treats when you have achieved something – whatever it is that you enjoy! This is closely linked to planning – but don’t just spend all your time relaxing, or doing nothing but work! It’s important to maintain diversity in life. If your boss expects you to work a 10 hour day, then make sure that you do (hopefully s/he won’t). But even then you have 14 hours each day to do other things (please try and get 7 hours of sleep – it will help to keep you fit and well)! I find that having a colour coded diary with a clear schedule helps me manage my life – even though I tend to work far too much! The trouble is I enjoy my work!

This is closely linked to planning – but don’t just spend all your time relaxing, or doing nothing but work! It’s important to maintain diversity in life. If your boss expects you to work a 10 hour day, then make sure that you do (hopefully s/he won’t). But even then you have 14 hours each day to do other things (please try and get 7 hours of sleep – it will help to keep you fit and well)! I find that having a colour coded diary with a clear schedule helps me manage my life – even though I tend to work far too much! The trouble is I enjoy my work! Many people who now have to work at home because of Covid-19 will not have had much experience previously at doing this. It can come as a shock getting to see other aspects of a loved one’s life. Tensions are bound to arise, especially if you are trying to work when your children are at home because school has been closed. It can help to have a thorough and transparent discussion between all members of a household (including the children) to set some ground rules for how you are going to manage the next few weeks and months. This can indeed be challenging, and will frequently require revisiting, but having some shared expectations can help reduce the tensions that are bound to arise. Listening (however difficult it is) often helps to lower tension.

Many people who now have to work at home because of Covid-19 will not have had much experience previously at doing this. It can come as a shock getting to see other aspects of a loved one’s life. Tensions are bound to arise, especially if you are trying to work when your children are at home because school has been closed. It can help to have a thorough and transparent discussion between all members of a household (including the children) to set some ground rules for how you are going to manage the next few weeks and months. This can indeed be challenging, and will frequently require revisiting, but having some shared expectations can help reduce the tensions that are bound to arise. Listening (however difficult it is) often helps to lower tension. The clothes we wear represent how we feel, but can also help shape those feelings. It is amazing what an effect it can have if you get dressed smartly when you are feeling low. Likewise, most people like to dress in more relaxed clothing when they stop working, and we don’t usually sleep in the same clothes that we have worn during the day. Just because you are working at home, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will work well in your pyjamas (and imagine if you are suddenly asked to join a conference call without time to change!). The simple message is that we should continue to take care of ourselves, just as if we were going out to work or to a party!

The clothes we wear represent how we feel, but can also help shape those feelings. It is amazing what an effect it can have if you get dressed smartly when you are feeling low. Likewise, most people like to dress in more relaxed clothing when they stop working, and we don’t usually sleep in the same clothes that we have worn during the day. Just because you are working at home, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will work well in your pyjamas (and imagine if you are suddenly asked to join a conference call without time to change!). The simple message is that we should continue to take care of ourselves, just as if we were going out to work or to a party! Enjoy the physicality of life. Don’t always feel you have to be online in case “work” wants to get in touch. None of us are that important. The world will get by perfectly well without us! There is a lot of evidence that being online late at night can also disturb our sleep patterns. Remember that although we are increasingly being programmed to believe that digital technology gives us much more freedom in how we work, it is actually mainly used by the owners of capital further to exploit their workforces by making them work longer hours for no extra pay!

Enjoy the physicality of life. Don’t always feel you have to be online in case “work” wants to get in touch. None of us are that important. The world will get by perfectly well without us! There is a lot of evidence that being online late at night can also disturb our sleep patterns. Remember that although we are increasingly being programmed to believe that digital technology gives us much more freedom in how we work, it is actually mainly used by the owners of capital further to exploit their workforces by making them work longer hours for no extra pay! Being self-isolated at home will mean that you have vastly more time on your hands than you can ever imagine (as long as you don’t work all day and night). Use it creatively to do something that you have always thought about doing, but never had the time before. Read those books that you always wanted to. Learn a musical instrument. Learn to speak a new language (Python or Mandarin). Take up painting. Discover how to cook delicious meals with limited resources. Photograph the wildlife in your garden. Grow your own vegetables. Make beer. Even just plan your next (or first) holiday.

Being self-isolated at home will mean that you have vastly more time on your hands than you can ever imagine (as long as you don’t work all day and night). Use it creatively to do something that you have always thought about doing, but never had the time before. Read those books that you always wanted to. Learn a musical instrument. Learn to speak a new language (Python or Mandarin). Take up painting. Discover how to cook delicious meals with limited resources. Photograph the wildlife in your garden. Grow your own vegetables. Make beer. Even just plan your next (or first) holiday. It was a great honour to have been invited – a few hours beforehand – to give one of the inaugural WSIS TalkX presentations last Thursday evening as

It was a great honour to have been invited – a few hours beforehand – to give one of the inaugural WSIS TalkX presentations last Thursday evening as